I recently visited Tate Modern and caught the Maria Bartuszova exhibition. No, I hadn’t heard of her either.

It could be that my knowledge of Eastern European 20th century, female artists is lacking. There again, it could be that our collective knowledge of Eastern European, 20th century, female, artists is lacking.

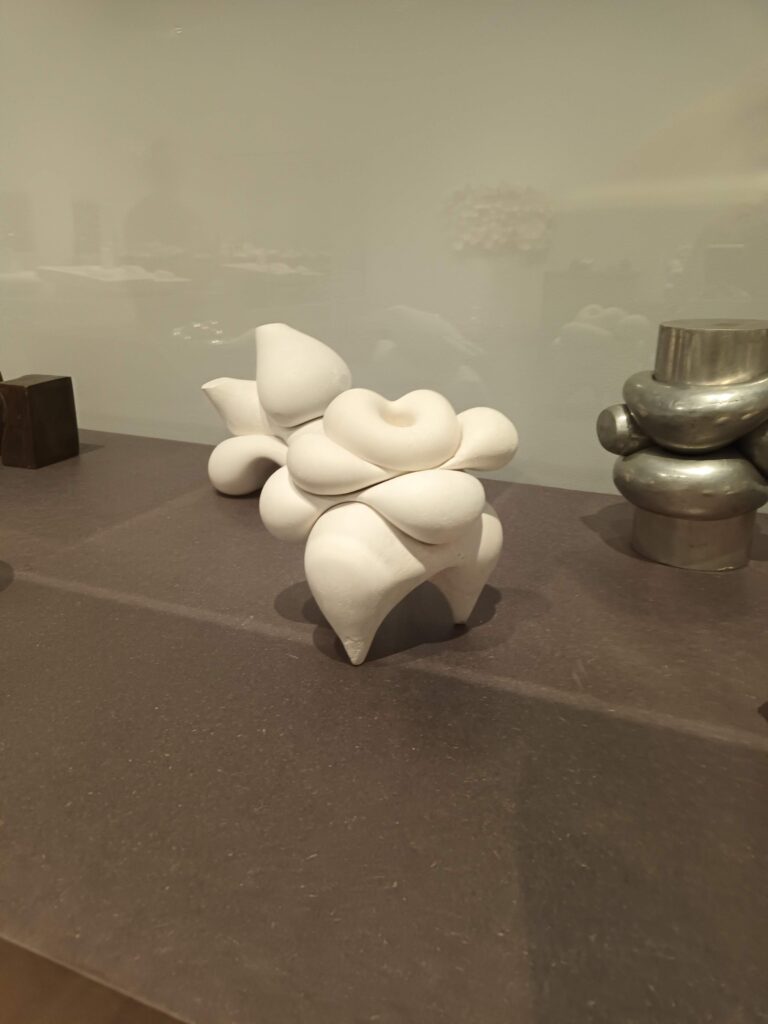

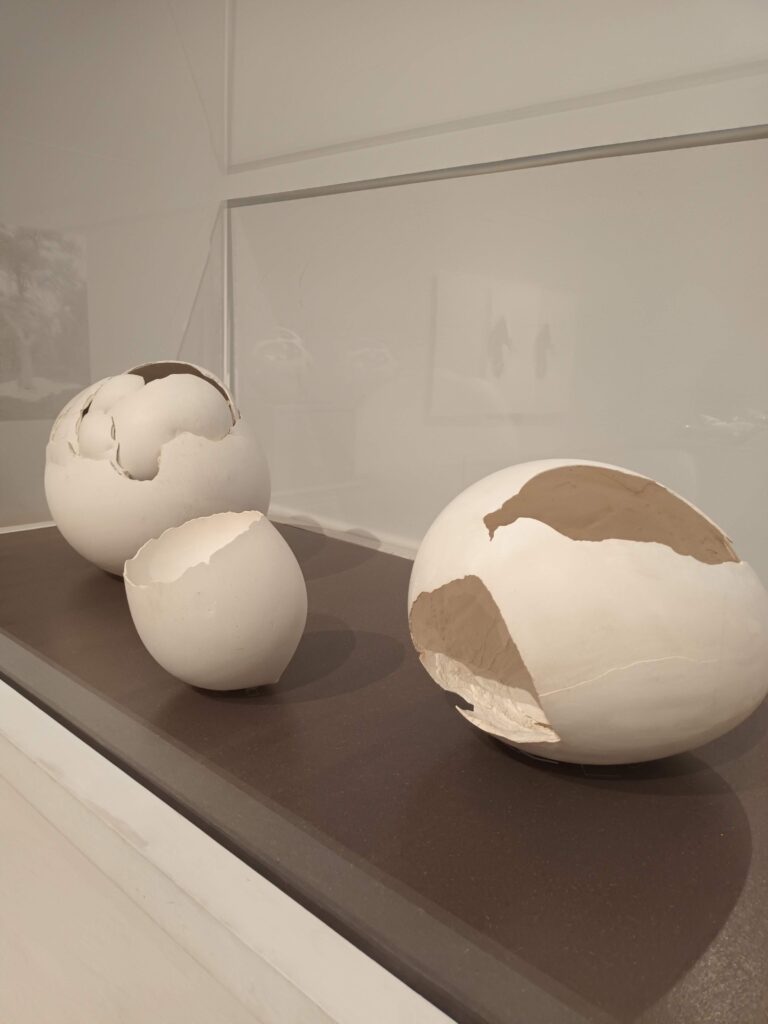

The exhibition was a revelation. Playful, exploratory, and joyful. Bartuszova used inexpensive materials (often plaster) to make shapes and clusters of forms, reminiscent of soft bodies, grains, seeds and eggs. There were ripenings, and breakings out and squidgings and connections and constraints and decompositions. It was very feminine, and yet not. Almost totally monochrome, with no extraneous decoration or ‘prettiness’. A lifetime of playing, meaningfully.

Bartuszova lived in what was then Czechoslovakia (she is described now as a Slovakian artist and was born in Prague in 1936), living mostly behind the Iron Curtain. She was commissioned to make public sculptures and street furniture (there are beautifully simple models for playground pieces in the exhibition), and also managed to make her own experimental work, whilst bringing up a family.

This seems incredibly modern for the mid 20th century and shows how, though the Western world talked the talk, the Eastern Bloc were walking the walk when it came to equality in the arts. Although, I’m sure this simple story belies the straight forward hard work and endeavour that was necessary of Bartuszova to make a living as a female, parent, artist, then as it would now.

The thing that struck me was that all Eastern Bloc artists were largely unknown outside of their respective countries. To be making a lifetime of meaningful and essential work, knowing that it’s influence would always be limited and constrained, must force an artist to really think about why they make.

I wondered if Bartuszova’s thought process around these constraints was to understand her and her works wider connection to the world, beyond politics and ideologies. The words ‘my breath is part of the universe pulsating’ are credited to her and show her deep connection to the world as a whole, not just her immediate environment. Indeed, the idea that artists must be well known, have a narrative to ‘their story’, even mythologised (think Picasso or Pollock), to be ‘successful’ is a very Western idea, and not always helpful.

The other way to deal with these constraints, is of course, to make art from them. By the 1980’s Bartuszova was divorced, living in Kosice and making work exploring pressed and bound forms. She wrote, “Ropes, cables, hoops, which sometimes tie up round shapes, can be a symbol of relationships between people, or of limited possibilities, or possibilities that limit what is alive”.

Bartuszova’s career also shows, I think, what amazingly self-contained and self-sufficient worlds these countries were at the time. From the outside looking in, they seemed limited in their outlook and influence (and were to an extent). Our view of them is also necessarily coloured by our knowledge of the surveillance and rules that their people lived under. But that doesn’t mean nothing good was produced in them.

I recently bought a book of lino and woodcut prints from North Korea. Yes, many of them are propagandist in nature and produced under strict government guidelines. But they’re also stunning in their artistry and design. An artist is an artist, whichever regime they’re living under. And it does not make them lesser people or artists if they choose not to resist a totalitarian regime with their art, but instead to keep making any way they can.

The North Korean artists within the book are supported and employed by the government. Yes, this necessarily means very strict rules and guidelines. But also the possibility of making beautiful art without the constant spectacle of poverty. I’m not suggesting these regimes are to be desired, but that it is not all black and white, good and evil. State sponsorship of the arts, is something to be desired, in my opinion.

Visited the Bartuszova exhibition reminded me of visiting the Elizabeth Frink exhibition at the Sainsbury’s Centre for the Arts in Norwich several years ago and also Barbara Hepworth’s house and studio in Cornwall. All have similarities, having carved a life of art and family out for themselves, all moved to the countryside to make, all were successful by anyone’s standards, enjoying public commissions and making their own work. All three chose art forms that involved the ‘heavy lifting’ usually associated with men. Hepworth and Frink suffered incredible patronisation and outright hostility for continuing to work and have children. Yet they all made work of, and with, their femininity and womanhood.

All three artists managed to fashion a good and creative life of their own. There are always constraints- it’s what you do with them that counts.