As a landscape artist I was interested to visit the Royal West of England Academy exhibition ‘Earth: Digging Deep in British Art 1781-2022’ (now finished). By chance, as is so often the way, I was also part way through ‘Spirit of Place: Artists, Writers and the British Landscape’ by Susan Owens. The two combined set me thinking about how we have changed our view of the landscape in which we live, through the centuries, and how we ‘see’ it differently.

‘Spirit of Place’ starts it’s journey much earlier than ‘Digging Deep’, and encompasses writers as well as visual artists. It takes in the Anglo Saxon monks- who almost literally turned away from the land, lest they would not be able to ‘hold to heavenly things’- through to the early cartographers, asking the questions: do we see the world differently once it’s mapped and measured? Are cartographers showing us the landscape they wish for? And to what purpose map-making? Can it change the landscape it maps? (another whole blog post I think!)

Before travelling through the 18th century, the book takes in the medieval vision of landscape as both full of mystery and the source of all life. By the time we reach the Romantic artists and writers of the 1700’s, we have entirely missed the fact that great swathes of the landscape of England, were, up until that point, seen as fearful and grotesque (including places we now ‘see’ as beautiful). Daniel Dafoe used words such as ‘horror’, ‘frightful’ and ‘terrible’ when describing mountains, for instance.

We have the Romantic posts and artists to thank for allowing us to ‘see’, and feel, a sublime vision of Britain.

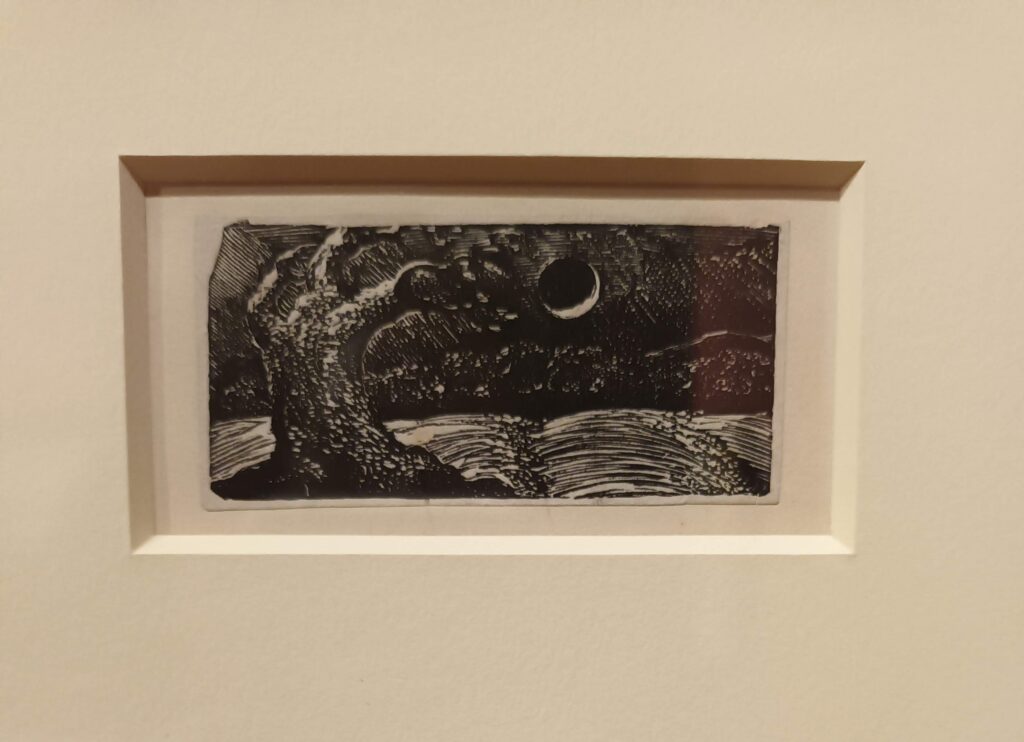

And this is where ‘Spirit of Place’ meets ‘Digging Deep’. The RWA’s smaller, darker, side gallery housed the small, and perhaps rather English, woodcuts of Blake and Calvert from the early 1800’s. After the pomp and grandiosity of the Romantic era, here was the English response, showing us a vision of the fecund farming landscape. These images have no lesser ideas in them, despite their size. This is a backdrop to what Blake and Calvert wished was there. In reality, the English countryside and it’s people were in dire straits at the time. The images beckon us to an optimistic vision, to use our imaginations to conjure up a land for our futures- something we perhaps all need to do at the moment.

My favourites in the final room of ‘Digging Deep’ were Eric Ravilious’ unsettling visions of pre-war ancient landscapes. His depiction of the land as both deeply ancient and etched by the modern world- and the joy in that juxtaposition- always quietly thrills me. His work, and much else in the exhibition reminds me of the Henry James quote about happiness being ‘speeding towards a 12c church in a motor car’.

By the late 20th C, constraints have fallen away, maybe because of the ease of communication between Britain and the rest of the world and the influence of non-British art, finally allowing our landscape to be viewed through a foreign lens as well. The large, airy main gallery at the RWA was given over to contemporary artist’s reflections of landscape. Here, the pieces that struck me were those that were literally made out of the earth, of earth. Andrew Hardwick’s piece straddles the line between painting and sculpture. Though his paintings of the landscape are mounted on the wall, they have become increasingly 3-D, as earth, pigment, mud and grasses are piled onto his boards. As his work grows larger, so the experience becomes more immersive.

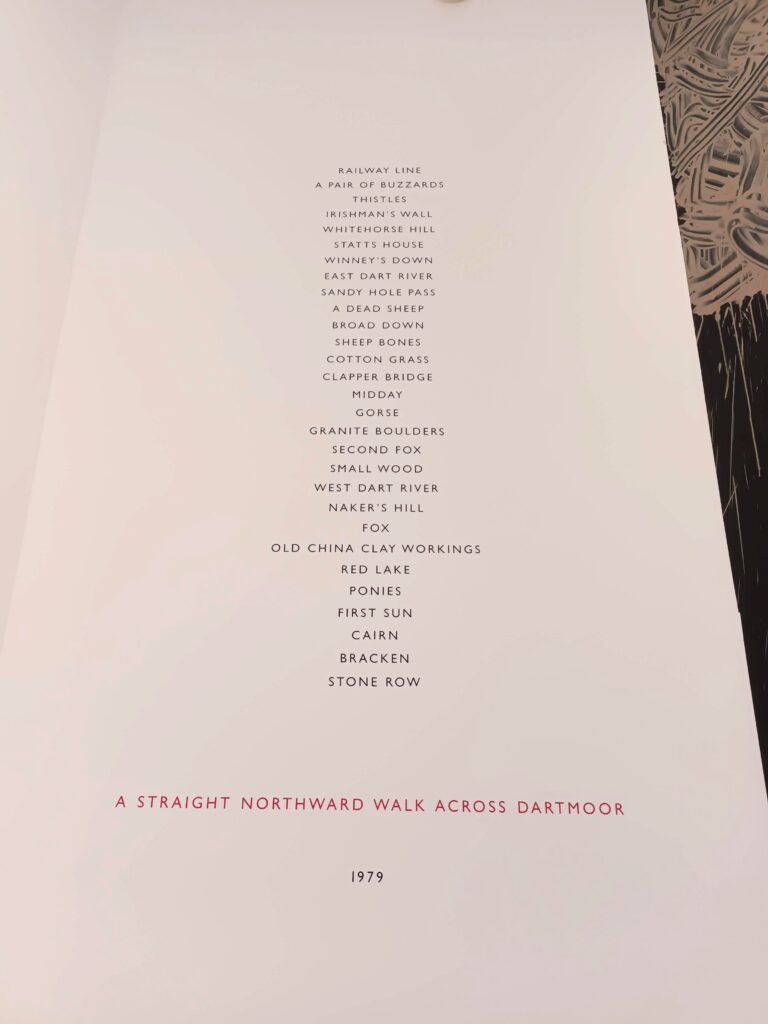

Talking of immersion, one of Richard Long’s hand made mud works dominated the far wall of the gallery, with splattered mud covering floor to ceiling, alongside two of his ‘walks’. One is ‘A Straight Walk Northward across Dartmoor’ from 1979, listing what he has noticed, in order, along his walk. This is a way of Long seeing the landscape without sentimentality, without what is supposed to be beautiful or pretty, or a good view, it records what is there, whether it’s a dead sheep, old china clay works or gorse. These are exciting in their new way of finding poetry and art in the landscape, in some ways much as the beat poets found it in their road trips.

Both the exhibition and the book reminded me how artists have ‘framed’ our earth for us so many times over the centuries, so that we can ‘see’ it from so many different angles, in reality and in vision, a cartography of our relationship to our earth. Seen as an overview, which both the book and exhibition attempt, a pattern of expansion and contraction can be felt, grandiosity and simplicity, imagination and reality. All these are needed at different times, and have revealed our landscape to us- no doubt more ways of seeing will come as our century continues.